Jan 26, 2015

Mega-Mergers Popular Again on Wall Street

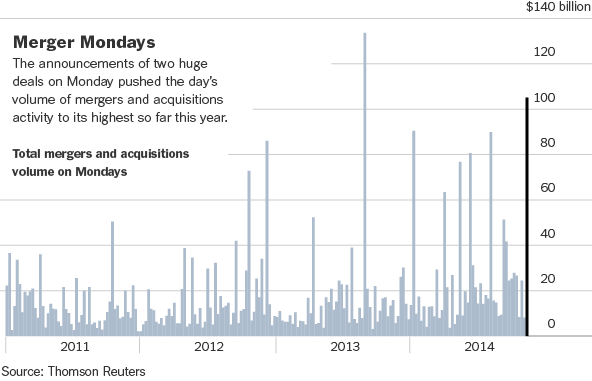

Global deal-making in 2014 has topped the $3 trillion mark in a year for only the fifth time and is up 50 percent from the same time a year ago, while acquisitions targeting American companies are up 65 percent, according to Thomson Reuters.

Yet there are some dark corners in the dazzling successes of Wall Street’s deal makers. Even as companies spend on mergers and acquisitions, they are not spending in other areas. Wage growth remains sluggish, and hiring is growing only modestly.Moreover, whether or not mergers and acquisitions are even a positive for the economy — and for the companies striking them — remains a subject of debate. Mergers also often create redundancies, which can lead to job cuts.

Yet there are some dark corners in the dazzling successes of Wall Street’s deal makers. Even as companies spend on mergers and acquisitions, they are not spending in other areas. Wage growth remains sluggish, and hiring is growing only modestly.Moreover, whether or not mergers and acquisitions are even a positive for the economy — and for the companies striking them — remains a subject of debate. Mergers also often create redundancies, which can lead to job cuts.“There is some evidence that deals may actually be detrimental to the economy, particularly these big bursts,” said Tara M. Sinclair, an associate professor of economics at George Washington University. “Economists are pretty divided as to whether they’re a good thing or a bad thing.”

Regulatory hurdles also threaten to complicate some of the most audacious mergers. Comcast’s proposed $45 billion takeover of Time Warner Cableremains under scrutiny by antitrust officials in Washington, who are examining whether the combination will hurt consumers.

In another instance, SoftBank, the Japanese firm that owns the wireless provider Sprint, backed away from a planned acquisition of T-Mobile USAafter it became convinced that the deal would not pass muster with antitrust regulators. And Halliburton’s deal for Baker Hughes could also draw a close look.

“The thing I’ve been anxious about all year is that some regulatory activity blocks one of these deals, and then the M.&A. recovery slows down,” said Gregg R. Lemkau, global co-head of mergers and acquisitions at Goldman Sachs. “No C.E.O. wants to do a ‘bet the company deal’ and not get it done, and regulatory scrutiny could be a roadblock to this continuing.”

Already, the Obama administration effectively scuttled one mega-deal. After a flurry of so-called inversions, in which American companies bought overseas competitors and moved their headquarters abroad to reduce their tax bills, the TreasuryDepartment in September announced rules targeting the transactions.

Weeks later, AbbVie, a drug maker based near Chicago, walked away from a $54 billion agreement to acquire its Irish rival Shire. Other inversions in the works were put off, and few such deals have been announced in recent months.

Nonetheless, the size and variety of deals being tried reflect a new sense of ambition among many of the world’s biggest companies.

“There is a frenzy for M.&A. that is driven in part by the low cost and accessibility of capital, and the need for consolidation in many industries,” said Brent Saunders, chief executive of Actavis, which on Monday struck the biggest deal of the year.

Many of the larger deals have been driven by sweeping changes that are shaking up entire industries. Drug makers like Pfizer and Actavis are on the hunt for new products to fill in gaps in their offerings. The health care industry is responsible for much of the surge in deal-making this year, producing $423.6 billion in announced deals, or nearly double the next-busiest year.

Telecommunications firms sought to bolster their footprints across the country and gain more negotiating power with content providers. Comcast’s agreement to buy Time Warner Cable was followed by AT&T’s agreement to buy DirecTV for $48.5 billion. Even media giants like 21st Century Fox, run by Rupert Murdoch, looked to deal making, in part to give them more clout to use against distributors.

And companies like social networks and cigarette makers also got involved. Reynolds American is seeking to buy a rival tobacco company, Lorillard, for $27.4 billion, and Facebook acquired WhatsApp for $21.8 billion.

Facebook, like many other big companies, paid for its acquisitions largely with its own stock, which has risen along with the broader market this year. Those companies that needed to borrow billions to pay for costly acquisitions were emboldened by interest rates, which remain near record lows and show no signs of rising soon.

Another factor fueling deal making this year has been the presence of activist hedge funds. William A. Ackman’s hedge fund Pershing Square Capital Management had been working with another company, Valeant, in an effort to buy Allergan, putting the Botox maker in play for its eventual sale to Actavis. And Carl C. Icahn has successfully agitated for the sale of a number of companies, including Family Dollar.

The previous two merger booms preceded sharp economic downturns. The dot-com bubble burst in 2001, and the leveraged buyout surge was scuttled by the financial crisis. But this time, bankers are not bracing for another downturn.

“The buildup here has been more disciplined, longer and more methodical, which hopefully means that it will continue,” said Blair W. Effron, co-founder of Centerview Partners, an independent investment bank that has advised on many of the year’s big deals.

Yet more than anything, it is the sense of relative stability that has unleashed Wall Street’s deal makers. And until that changes — in the form of a stock market crash or another debt crisis — the merger boom seems likely to continue.

“This is another consistent piece of information that the economy really is doing well right now,” Ms. Sinclair, the economics professor, said. “But there’s also reason to be slightly concerned. When you see a bunch of deals all at once, you wonder that if this is, once again, irrational exuberance.”

Global deal-making in 2014 has topped the $3 trillion mark in a year for only the fifth time and is up 50 percent from the same time a year ago, while acquisitions targeting American companies are up 65 percent, according to Thomson Reuters.

Yet there are some dark corners in the dazzling successes of Wall Street’s deal makers. Even as companies spend on mergers and acquisitions, they are not spending in other areas. Wage growth remains sluggish, and hiring is growing only modestly.

Moreover, whether or not mergers and acquisitions are even a positive for the economy — and for the companies striking them — remains a subject of debate. Mergers also often create redundancies, which can lead to job cuts.

“There is some evidence that deals may actually be detrimental to the economy, particularly these big bursts,” said Tara M. Sinclair, an associate professor of economics at George Washington University. “Economists are pretty divided as to whether they’re a good thing or a bad thing.”

Regulatory hurdles also threaten to complicate some of the most audacious mergers. Comcast’s proposed $45 billion takeover of Time Warner Cableremains under scrutiny by antitrust officials in Washington, who are examining whether the combination will hurt consumers.

In another instance, SoftBank, the Japanese firm that owns the wireless provider Sprint, backed away from a planned acquisition of T-Mobile USAafter it became convinced that the deal would not pass muster with antitrust regulators. And Halliburton’s deal for Baker Hughes could also draw a close look.

“The thing I’ve been anxious about all year is that some regulatory activity blocks one of these deals, and then the M.&A. recovery slows down,” said Gregg R. Lemkau, global co-head of mergers and acquisitions at Goldman Sachs. “No C.E.O. wants to do a ‘bet the company deal’ and not get it done, and regulatory scrutiny could be a roadblock to this continuing.”

Already, the Obama administration effectively scuttled one mega-deal. After a flurry of so-called inversions, in which American companies bought overseas competitors and moved their headquarters abroad to reduce their tax bills, the TreasuryDepartment in September announced rules targeting the transactions.

Weeks later, AbbVie, a drug maker based near Chicago, walked away from a $54 billion agreement to acquire its Irish rival Shire. Other inversions in the works were put off, and few such deals have been announced in recent months.

Nonetheless, the size and variety of deals being tried reflect a new sense of ambition among many of the world’s biggest companies.

“There is a frenzy for M.&A. that is driven in part by the low cost and accessibility of capital, and the need for consolidation in many industries,” said Brent Saunders, chief executive of Actavis, which on Monday struck the biggest deal of the year.

Many of the larger deals have been driven by sweeping changes that are shaking up entire industries. Drug makers like Pfizer and Actavis are on the hunt for new products to fill in gaps in their offerings. The health care industry is responsible for much of the surge in deal-making this year, producing $423.6 billion in announced deals, or nearly double the next-busiest year.

Telecommunications firms sought to bolster their footprints across the country and gain more negotiating power with content providers. Comcast’s agreement to buy Time Warner Cable was followed by AT&T’s agreement to buy DirecTV for $48.5 billion. Even media giants like 21st Century Fox, run by Rupert Murdoch, looked to deal making, in part to give them more clout to use against distributors.

Another factor fueling deal making this year has been the presence of activist hedge funds. William A. Ackman’s hedge fund Pershing Square Capital Management had been working with another company, Valeant, in an effort to buy Allergan, putting the Botox maker in play for its eventual sale to Actavis. And Carl C. Icahn has successfully agitated for the sale of a number of companies, including Family Dollar.

The previous two merger booms preceded sharp economic downturns. The dot-com bubble burst in 2001, and the leveraged buyout surge was scuttled by the financial crisis. But this time, bankers are not bracing for another downturn.

“The buildup here has been more disciplined, longer and more methodical, which hopefully means that it will continue,” said Blair W. Effron, co-founder of Centerview Partners, an independent investment bank that has advised on many of the year’s big deals.

Yet more than anything, it is the sense of relative stability that has unleashed Wall Street’s deal makers. And until that changes — in the form of a stock market crash or another debt crisis — the merger boom seems likely to continue.

“This is another consistent piece of information that the economy really is doing well right now,” Ms. Sinclair, the economics professor, said. “But there’s also reason to be slightly concerned. When you see a bunch of deals all at once, you wonder that if this is, once again, irrational exuberance.”

Tags